|

Submit Paper * Editorial Team * Tracks * Guideline * Standards for Authors/Editors * Accepted Papers' List Members * Participating Universities * Editorial Policies * Cambridge Research Library * Publication Ethics * Chairs |

|

|

|

The Pen (The Written Word) vs. Video |

|

Throughout history, the pen has always been linked with writing. As you well know, it helps the writer to record his or her thoughts on paper. The sword is a weapon used forcefully against someone. The pen is utilized by civil society, while the sword is used by primitive minds. Lately, there has been a controversy brewing on the written word vs. video. The heated debate erupted when techies began to foretell the demise of the written word.

Many great writers have inspired revolutions for the betterment of the people. The French Revolution, for example, was the result of the writings of great French activists like Jean Jacques Rousseau. Effective writings can evoke different emotions as love, harmony, sympathy, solidarity, hatred, etc. to rally people to a cause. It is something that is to be regarded with awe and respect. Hence the pen is considered a mightier device than the sword.

One of the executives, Nicola Mendelsohn, of Facebook recently has declared at a Fortune conference in London, that her platform will probably be all video and that the written word will be essentially dead. The rationale behind that prognostication is the contention that the best way to tell stories in this world, where so much information is being thrown at us, actually is through video. This medium conveys so much more information in a much quicker span of time to help us digest much more information.

Writers such as journalists use the pen to inform and influence readers. The pen and the journalist are congenital twins. The profession of journalism is demanding in terms of time, money and energy. Unlike most professions, publishers of newspapers spent many sleepless hours, they are stressed out to meet deadlines, they are on a mission to find relevant news and stories, they are faced with the challenge of weak, if not dwindling, circulation, they struggle to find the time and the peace of mind to write their columns, comments, and editorials day in and day out. Likewise, publishers of academic journals go through the same agonizing struggles to bring forth a professional issue day in and day out.

Moreover, journalists and academic journal publishers need to find time and energy to respond to the readers' and subscribers' inquiries. I know all these exigencies for once I served as the editor of an international journal. All that work, only to find out that the readers are dwindling when it comes to the printed written word. Some say the Internet is taking over and busting the glory of the written word.

For ages, the pen has been mightier than the sword. Can it be possible that the pen is being replaced by the electronic voice or videos. Here are some examples of quotes in praise of the pen, namely the written word:

The proverb that "The pen is mightier than the sword" is a metonymic adage indicating that communication, or in some interpretations, administrative power, is a more effective tool than direct violence (through the sword). The sentence was coined by the English author Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1839 for his play Richelieu: Or the Conspiracy. However, the idea had been expressed in various earlier forms from antiquity. Here are some examples of the precursors of Bulwer-Lytton's statement:

The Assyrian sage Ahiqar, who supposedly lived during the early 7th century B.C., coined the first known version of this phrase. One copy of the Teachings of Ahiqar, dating to about 500 B.C., states that "The word is mightier than the sword."

The Prophet Muhammad is quoted as saying "The ink of the scholar is holier than the blood of the martyr." This saying is attributed to Muhammad even though he was completely illiterate.

William Shakespeare in 1600, in his play Hamlet Act 2, scene II, wrote: "... many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose quills."

Robert Burton, in 1621, in The Anatomy of Melancholy, stated: "It is an old saying: A blow with a word strikes deeper than a blow with a sword." After listing several historical examples he concludes: "From this it is clear how much more cruel the pen may be than the sword."

Thomas Jefferson, on June 19, 1792, ended a letter to Thomas Paine with: "Go on then in doing with your pen what in other times was done with the sword: show that reformation is more practicable by operating on the mind than on the body of man, and be assured that it has not a more sincere votary nor you a more ardent well-wisher than Y[ou]rs. &c. Thomas Jefferson"

Published in 1830, by Joseph Smith, Jr.an account in the Book of Mormon related, "...the word had a greater tendency to lead the people to do that which was just; yea, it had more powerful effect upon the minds of the people than the sword."

Netizens have suggested that a 1571 edition of Erasmus' Institution of a Christian Prince contains the words "There is no sword to be feared more than the learned pen."

The French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), known to history for his many military conquests, also left this often-quoted remark: “Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets.” He also said: "There are only two powers in the world, saber and mind; at the end, saber is always defeated by mind."

During the past few years, the crisis in journalism has reached new heights. Unquestionably, a time will come when some major cities will no longer have a newspaper and when magazines and network-news operations will employ no more than a handful of reporters. As for academic journals, the demand is also dwindling despite the fact that a pen is a precious thing to waste! But does this herald the death of the written word?

After Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 1450s, books became within the reach of the average person. Later, Aldus Manutius, the Renaissance Venetian printer, invented the pocket-sized book that penetrated all segments of the reading market. Books enjoyed popularity for many years, until the advent of the computer.

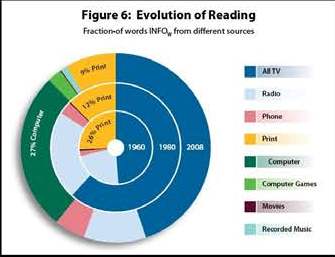

As can be observed in Figure 6 below, the evolution of reading among other media or platforms was 26 percent in 1960, then it became 12 percent in 1980, and it dwindled further to 9 percent in 2008. It is expected that reading will decline further in the near future. In other words, death is on the horizon for the printed word. Many claim the written word will die out very soon. In fact, they claim it is well on track as people read less, and writing skills become redundant.

Diagram prepared by Eliot Van Buskirk

There seems to be two main schools of thought: The "doomsday group" and the "forever group" when it comes to the written word. The first school maintains that the written word is in a death spiral. YouTube, videogames, cable TV and iPods have turned us away from the written word. Moving visual delights replaced paper and longhand letters shrank to bite-sized Facebook status updates. While the second school holds the view that unless our civilization fundamentally collapses, we will never give up writing and reading.

Both schools seem to subscribe to extreme views such as death or alive situation for the written word. Years ago, when radio came about, they predicted the death of the conventional school. Students will stay home and get their education from the radio. That outlook failed to materialize as predicated. When the computer entered our world, on-line learning was predicted to replace conventional colleges and universities. Well, while we do have distant learning based on the computer technology, it has yet to replace our colleges and universities.

A middle ground prognostication would be safer when we are dealing with either or situation. Thus, the evaluation of the word or text vs. the video should be on a contingency basis. Apart from the platform used, the preference of the individual is important. For example, there are people that grasp better when they read, while others do better visually when watching a video.

While visual platforms will increase in use, they will not cause the demise of the written word. Obtaining useable information from video vs. text presents different challenges. Video is a linear medium: one has to allow it to "unspool," unwind frame by frame to glean what it is saying; while text can be absorbed in blocks, sequentially or recursively, as the human eye searches for keywords or concepts. Also, text is generally searchable online while the video can be searchable, but it presents time-consuming challenge to transcript keyed to points in the video.

Anyone who engages in research and writing has found out that it is much easier to learn from text than by watching a video on a topic of interest. Reading elicits the left hemisphere of the brain which is wired for comprehension and retention (i.e., for high-involvement learning which influences long-term memory) while viewing a video triggers the right hemisphere of the brain which is for enjoyment (i.e., low-involvement learning which influences short-term memory).

Additionally, one can easily search for information in text; one can easily jump over passages that are not of relevant to the topic being searched. Moreover, one can read faster and understand the written word than if the video speed is increased rendering understanding difficult. Finally, one can adapt to the speed of reading to the complexity of the text, while in video one has to pause or rewind the tape. Video is great for leisurely viewing and reading is for serious researching and writing. Since the Sumerian times, the written word has kept its use for over five thousand years while the video is a new kid on the block with only unsubstantiated claims to hand the death sentence to the written word. The jury is out yet on the likelihood of video replacing the written word.

Z. S. Demirdjian, Ph.D. Senior Review Editor California State University, Long Beach

|